To Avert Disaster, Peru Diverts Water Fees To Andean Alpacas And Pre-Incan Aqueducts

Lima made headlines this year when it announced it was restoring pre-Incan canals high in the Andes to address its water shortage. That, however, is just one small part of a nationwide shift towards “green infrastructure” that blends the natural ecosystem of the high Andes with man-made technologies old and new. To make it happen, the country first had to change the way it pays for clean water.

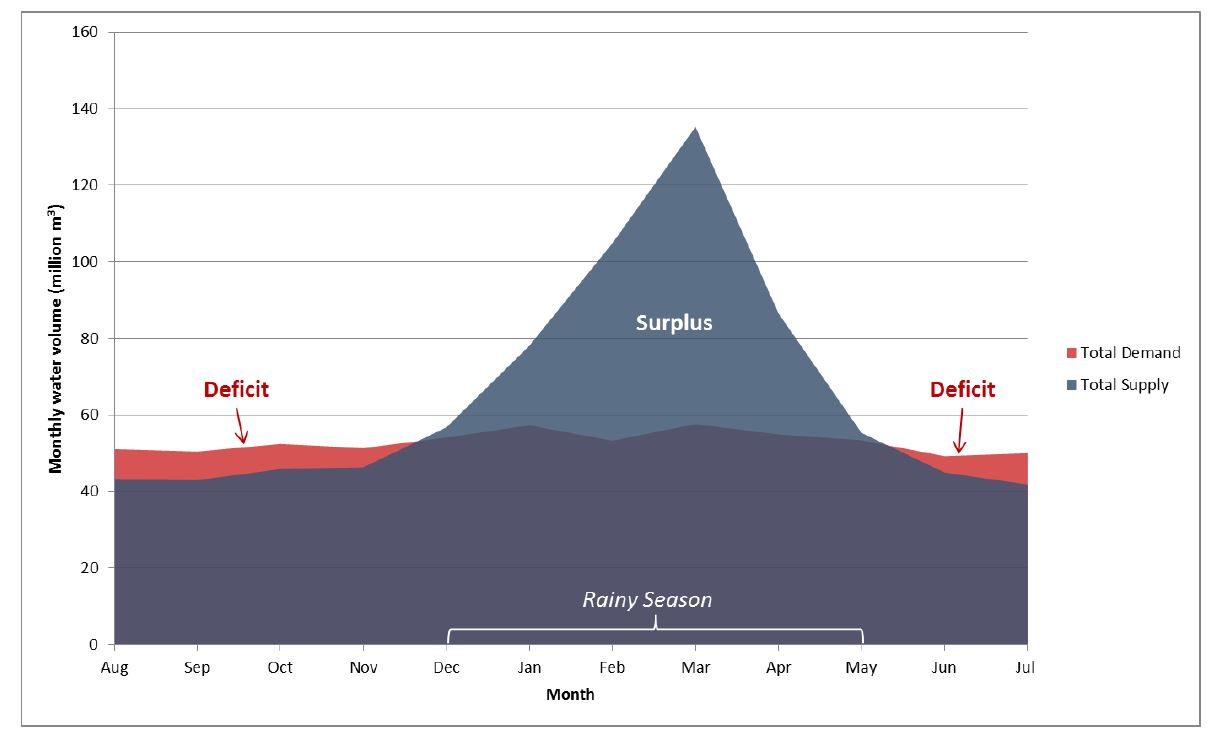

This spring, massive landslides swept down the Andes, killing nine people just above Peru’s capital, Lima, and destroying the homes of hundreds more. Then came the dry season, and Lima – the world’s second-largest desert city – went thirsty, as it always does for seven months each year. But the city also made headlines for its decision to smooth those cycles by embracing radical “new” green solutions that harken back one thousand years.

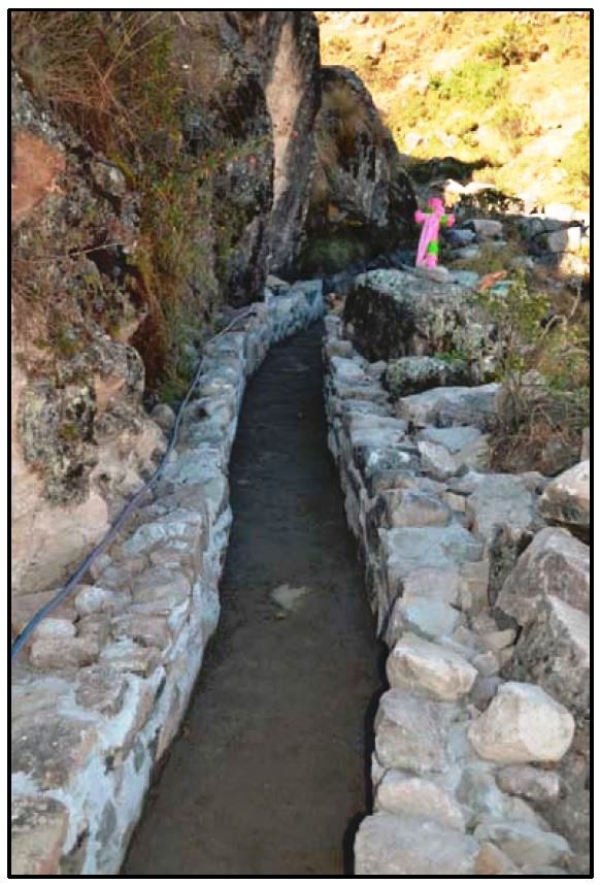

Yes, one thousand years. That is when a pre-Incan people carved stone canals into the Andes to absorb the five-month wet season’s downpours and channel the water into the mountain, where it trickles down over a period of months instead of hours to emerge in the dry season, when it’s needed most.

The Dilemma: Lima runs wet and dry.

In June, the government announced it was funneling $112 million of Lima’s water fees – or almost 5% of the total – into programs designed to help the Andes adapt to climate change and offer water quality improvements, with $26 million of that going into “green infrastructure” programs that include the restoration of these ancient structures – called “amunas”, and that investment is just the beginning.

Over the next three years, all 50 water utilities in the nation of Peru are expected to incorporate green investments that compliment typical grey, engineering solutions. This comes thanks to a surprising combination of allies, advocates and recent studies that document the value of incorporating green infrastructure. Now, in this technocratic world of water, together they are breaking down the dam of conservative solutions that for so long resisted change.

Green Infrastructure

With “green infrastructure”, cities use nature to filter water, manage floods, and otherwise meet citizen’s water needs. In addition to restoring the amunas, for example, Lima will undertake other efforts to restore its mountain catchments – including some as simple as encouraging farmers to abandon cows and sheep in favor of native alpacas. The reason? Alpacas have soft, padded hooves like house slippers, and those hooves don’t pound the water-absorbent dirt into an impenetrable hard surface the way cows and sheep do. Alpacas even graze in ways that are eco-friendly: they snip the grass with their teeth, so its roots stay to maintain the soil, while cows and sheep yank it out, roots and all. Alpacas, in other words, mean soil absorbs water instead of repelling it, so it comes down the slopes more slowly than usual.

The methods may seem romantic, and in a sense they are, but they also make solid economic sense. The decision to go green is backed by a cost-curve analysis that’s gaining traction among financiers and governments looking for effective ways to make clean water readily available.

The Economics of Green Infrastructure

Entitled “Assessing Green Interventions for the Water Supply of Lima, Peru,” the cost-curve analysis was prepared early last year by Ecosystem Marketplace publisher Forest Trends, Peruvian NGO CONDESAN, environmental engineering firm Kieser & Associates and the water fund Aquafondo. It draws on the expertise of hydrologists, environmentalists and engineers to evaluate green solutions. And, sure enough, these green solutions turn out to have bargain-basement prices when compared with typical “gray” infrastructure projects.

The analysis proved so valuable that it may be copied throughout Peru and can be adapted to address environmental challenges worldwide. But moving from paper to projects remains a challenge. A look at the history and hurdles of conquering chronic water shortages tackled by Lima offers a microcosm into the analysis’ potential as well as its pitfalls worldwide.

“It’s still a puzzle to fill out,” says Gena Gammie who co-authored the analysis, “a Rubik’s Cube to twist around until all the parts line up.”

Pulling the Trigger

Key to lining up the parts was an unlikely environmental hero, a lawyer-turned-bureaucrat named Fernando Momiy.

“It was just a matter of common sense,” says Momiy, president of Peru’s national water regulator, SUNASS. “And it was just a matter of money.”

Momiy pieced together an improbable assembly of tax collectors, bureaucrats, economists, environmentalists, engineers, and do-gooders determined to protect indigenous farmers. Together they determined that, while million-dollar reservoirs and miles of piping had not solved their water problems, supplementing this with cheap, green solutions could. Then they began pitching the people of Lima on the idea of sending some money from their water bills up into the Andes.

“It was an aligning of the stars,” says Marta Echavarría who specializes in developing emerging markets for ecosystem services. “Now there is an institutional and financial vehicle to do the work. And that is huge.”

No Newcomer

Momiy, it turns out, is no stranger to innovative financing. Years ago, he worked as general manager under the leadership of then-SUNASS President Jose Salazar. At that time, residents in the downstream city of Moyobamba in northern Peru had been plagued with alternating droughts, floods, landslides and pollution – much as Lima is today. Moyobamba residents agreed to pay SUNASS, their water supplier, a small additional tax to reforest and repair land upstream.

It’s an effort that builds and improves on earlier programs. New York City, for example, has protected land as far north as Lake Tear of the Clouds in the Catskill Mountains for decades to allow clean water to flow into city sinks. In Quito, Ecuador, residents pay an extra two cents on every dollar taxed for water to pay for green solutions. And in Colombia they pay an extra six cents per dollar. Now, with Peru’s success in Moyobamba, there were enough projects to demonstrate that green solutions, when combined with conventional gray infrastructure, can offer the critical missing link to make clean, abundant water available.

After becoming president of SUNASS, Momiy persuaded the ancient Incan capital of Cusco to implement a similar program, generating similar results – but that was just two of Peru’s many cities.

“You need more than an idea,” he says. “You need something to push the idea to reach the goal. This is a key point.”

That meant turning the idea into a law.

A New National Water Regime

This is when the story really heats up. The Peruvian Congress began developing its new water resources management law and sent it to SUNASS for comment. Realizing his opportunity, Momiy slipped in a short but key paragraph that said water operators should invest in green infrastructure projects.

That paragraph matters, because all water utilities undergo reviews of their tariffs and budgets every five years, and now each public water company in Peru will be asked to invest a small part of tariffs collected – a few cents on every dollar – in projects that preserve, enhance and minimize pollutants in watersheds from where their water comes.

The law passed through Congress in 2013, and the following week, Lima – one of the first to fall under this new review – approved the tariff.

“This new law is so powerful; it’s the stone on which we can build a solid house,” Momiy says. “And that’s what we’re building now.”

Not only will Lima residents begin paying a small tax to invest in conservation projects like repairing its ancient canals and upstream pastures but also, during the next four and a half years, water utilities throughout Peru will be mandated to adopt budgets that consider green infrastructure as part of their water-availability solutions.

“What we are developing is a buffet of solutions,” Momiy says. “Some depend on typical ‘gray’ infrastructure, and some depend on green ones. The challenge is to put accurate dollar figures on the costs and then convince people that they work.”

Incubating Solutions

Clearly, neither green nor gray solutions by themselves were enough to solve Lima’s water shortage. So Forest Trends began teaming with Peru’s Ministry of the Environment in 2012 to create a “National Incubator,” a rapid hydrological diagnostic tool that actually put a dollar cost on various alternatives, from desalinating water from the nearby ocean to restoring the amuna canals. Then the cost-curve analysis released last year hit the ball home, focusing on four specific green interventions that could increase the amount of water that reaches thirsty Lima.

Potential interventions include keeping animals off upstream grasslands, rotating grazing, restoring upstream wetlands and rebuilding the ancient “amunas” channels. The analysis also looks at towns that already implemented green hydrological solutions. Then it assesses material and labor costs. And it compares these with potential gains in water quantity.

“In the past we just said it would work but never tried to measure how well it would work,” says Alberto Gonzales of The Nature Conservancy. “Now, for the first time ever, we’re able to identify specific hydrological gains.”

What’s Next?

While all the green options proved cost effective, history lovers will be happy to hear that restoring ancient canals stood out as by far the best. In fact, the next best option, restoring wetlands, turned out to be ten times as expensive. And all green options proved far less expensive than their gray alternatives.

Of course, most thirsty towns do not have pre-Incan canals waiting for restoration. They also may not have cowboys who, for generations, allowed their cattle to graze – and overgraze – freely in hills upstream and need to be compensated to change this pattern. Upstream slopes, development and a host of other variables will have to be considered to determine the costs of green interventions in varied locals. Even the Lima analysis is still an effort in progress. It takes at least a five-six year time horizon to get robust results because of rainfall variability from year to year.

“To measure how this intervention works, the real hydrological impact, is a big challenge,” says Oscar Angulo, a hydrologist for CONDESAN, the NGO that helped write the cost-curve analysis. “We’re still in the process of finding out.”

As a result, only one of at least 50 known ancient canals has been restored. Meanwhile, negotiations with owners of upstream cattle continue.

The delay is not surprising for those familiar with the conservative outlook that typically characterizes water utilities. That they are now considering green investments is remarkable, says Gammie who is working on a case study about this for Forest Trends that she expects to release this December.

“We’re just at the beginning,” says Echavarría. “We know the tariffs will not be enough to cover the investment required to protect watersheds, so we can bring money in from other sources, from the private sector and water funds like Aquafondo, financial vehicles that allow us to leverage resources and ensure accountability.”

Getting the Cost of Water Right

Going forward, Forest Trends is working with local partners and leading experts to develop guidelines that can be executed efficiently, transparently, effectively and on a project-by-project basis, Gammie says.

But, she adds, “There clearly still is inertia that gets in the way of green solutions. There’s an opening but we’re not quite there yet.”

Yet, thanks to the work in Lima, the dam of inertia that, until recently, held back green solutions has not only been breached, it has released a flood of potential. In April 2015, Momiy, on behalf of SUNASS, shared Lima’s success with water regulators worldwide at the World Water Forum in South Korea. And in December 2015, the Association of all Latin American Regulators will meet and hear more about this from the Latin association’s current president. And yes; the association’s president is, once again, Momiy.

“We are going to have storms in the way but we have to work at it,” he says. “It’s not just about protecting the environment. It’s about being better off economically. This is a good investment.”

Edited by Steve Zwick

Alice Kenny is a prize-winning science writer and a regular contributor to Ecosystem Marketplace. She may be reached at alicekenny1@gmail.com.

Facebook comments