Hunger in Shangri-La: Causes and Consequences of Food Insecurity in the World’s Mountains

Over the past decade, the number of undernourished people around the world has declined by around 167 million, to just under 800 million people. However, this positive trend glosses over a stark reality: Food insecurity is increasing in the world’s mountains. This pattern has been under-recognized by development experts and governments, a dangerous oversight with far-reaching social and environmental repercussions.

Thomas Hofer, coordinator of the United Nation’s Mountain Partnership, recently presented findings on the vulnerability of mountain people to permanent representatives and key stakeholders at the UN in New York City. The statistics were stark and the audience somber.

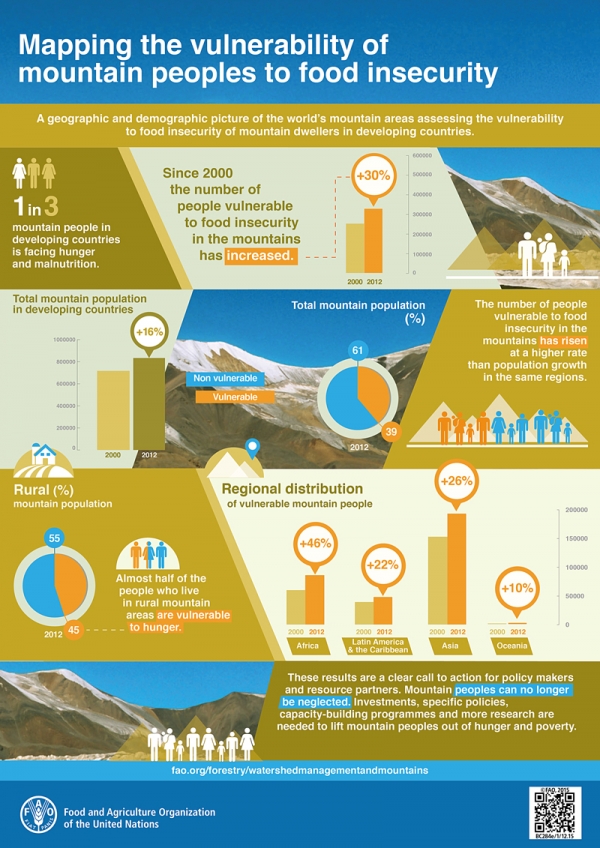

As of 2012, the most recent year for which a full dataset was available, an estimated 329 million people living in mountainous regions of developing countries – including nearly half the rural population – were vulnerable to food insecurity. These mountain people “lacked secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life.” The UN Food and Agriculture Organization further found that the number of hungry mountain people had increased by 30 percent over the previous 12 years.

While food security in the rest of the world has generally been improving, it’s been getting worse in the mountains.

Putting this into context, the world’s mountains are home to about 13 percent of humanity and cover some 22 percent of Earth’s land area, yet in 2012 they contained nearly 40 percent of the world’s food-insecure people.

The trend is worse still because the report almost certainly underestimates the problem. FAO’s threshold for classifying a population as vulnerable to food insecurity was a daily consumption of less than 1,370 calories and 14 grams of protein per person. This is a minimum survival requirement, barely enough to sustain someone in a warm, lowland climate. Any trekker knows that many more calories are required to keep energetic and warm in high and cold lands. At an altitude of 10,000 feet, a hard working farmer or pastoralist could easily require more than 3,000 calories a day.

Moreover, globalization, development assistance, and food aid are in some cases moving communities from traditional diets, rich in whole grains and other nutritious local foods, to lower-protein processed cereals and less nutritious diets generally. This is not unique to mountains, but can have serious impacts for people already on the edge of hunger.

The impact of poor diets cascades through mountain societies to reduce productivity, affect health – especially of children – and limit capacity to adapt to a fast-changing world.

Why Is Food Insecurity Increasing in Mountains?There are many interrelated factors behind this troubling trend:

* Growing populations. Human numbers in mountains in developing countries increased about 16 percent between 2000 and 2012, straining natural resources and the productive capacity of highland ecosystems in some places. Population pressures on mountain ecosystems will likely increase as climate change advances and people move upland to escape heat and drought. This is already happening in parts of Africa and Asia.

* Youth exodus. While populations may be increasing overall, there is a massive out-migration of young people seeking a better life from rural mountain areas to urban centers or abroad, particularly men. This type of migration leaves fewer strong workers to cultivate food crops, care for livestock, and generate income in other ways. We already know this is placing an extra burden on the women, children, and elderly who are left behind.

* Chronic invisibility. Throughout the developing world, mountain communities are underserved by governments and other providers of social services. Many are ethnic minorities with little political influence located in remote areas. Meanwhile, mountain-relevant policies are typically set by and for the benefit of more powerful lowland interests.

From the private sector, investment in mountains tends to focus on natural resource extraction, from mining to timber and hydropower. Where governance is weak and non-inclusive, such enterprises may provide few benefits to local people and often trample on their rights.

* Environmental change. Many mountain environments are severely degraded ecologically. This, in turn, hampers the ability of mountain peoples to produce food and prosper, let alone protect the biodiversity and essential ecosystems services upon which they rely.

We know that rural mountain communities are among the most hard-hit by climate change – via effects like increased temperatures, fluctuations in precipitation, and changes to glaciers and snow pack – and among the most vulnerable to natural disasters. Is it any wonder that food production is under stress?

* Neglect by the development community. Rough mountain terrain, isolation, and low population density lead some to assume that development assistance is too expensive for too few beneficiaries. This thinking does not consider the co-benefits for lowlanders. More than half of humanity relies on freshwater that flows from mountain regions. There is therefore a clear incentive to ensure mountain ecosystems are well managed in order to secure the sustainable development of both highland and lowland people, agriculture and industry.

Moreover, The Mountain Institute and other groups have found cost-effective ways to build highland prosperity through unique and high-value products and services. These sustainable livelihoods projects include cultivating medicinal and aromatic plants and developing ecotourism, some with quite favorable returns on investment.

Facebook comments