Peru’s first-ever high-resolution carbon map could help the world breathe easier

To put an accurate price on carbon, you need to know how much you have and where it’s located, researchers say

Review the complete report in English: The High-Resolution Carbon Geography of Perú: A Collaborative Report of the Carnegie Airborne Observatory and the Ministry of Environment of Peru

►ftp://dge.stanford.edu/pub/asner/carbonreport/CarnegiePeruCarbonReport-English.pdf

Review the complete report in Spanish: La Geografía del Carbono en Alta Resolución del Perú: Un Informe Conjunto del Observatorio Aéreo Carnegie y el Ministerio del Ambiente del Perú

►ftp://dge.stanford.edu/pub/asner/carbonreport/CarnegiePeruCarbonReport-Spanish.pdf

Stanford University scientists have produced the first-ever high-resolution carbon geography of Peru, a country whose tropical forests are among the world’s most vital in terms of mitigating the global impact of climate change.

Released today, the 69-page report to Peru’s Ministry of the Environment could become a tool itself to battle rising temperatures. It is complete with vivid 3-D maps that pinpoint with a high degree of certainty the carbon density of Peru’s vast and varied landscape, from its western deserts and savannas, to its lowland forests, to its soaring Andean peaks, to its lush eastern Amazon rainforests.

The maps also reveal in sharp detail what’s missing: large swaths of once carbon-laden jungles now stripped bare by the extraction industry. Many of Peru’s gold, copper and silver mines operate legally; many of them do not. Environmental devastation is often the result.

The report represents two years of intensive aerial surveying by Greg Asner, a global ecologist with the Carnegie Institute for Science at Stanford University, and his team that operates the Carnegie Airborne Observatory (CAO).

The CAO is a twin-engine turboprop Dornier 228 filled with more than $10 million in the latest short-wave and infrared sensors. Those tools can scan as much as 100,000 hectares (240,000 acres) a day at a density of just one hectare (2.4 acres). At that level of precision, the data reveal not only the height of the trees below, but also the individual leaves on each tree as well as the chemical activity in all those leaves.

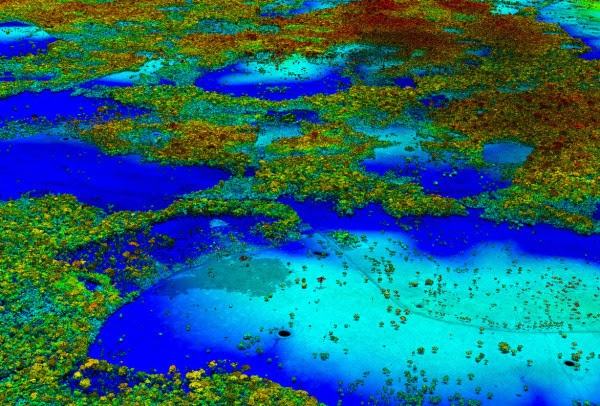

Asner’s team sampled 16 million acres of ecosystems within Peru’s 320-million total acreage. Those samples were scaled up to a country-wide map using field plots and existing satellite imagery. Colors in the national map indicate how much carbon is stored above ground. The scale goes from blue — zero carbon — to dark red in the highest areas.

The report found, for example, that 53 percent of all Peruvian carbon is stored in one large Amazonian region — Loreto, followed by Ucayali and Madre de Dios (26 percent combined).

Asner’s report emphasizes its underlying motivation and connection to climate-change mitigation: if global markets are going to value carbon at a competitive rate as an incentive to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, countries like Peru will need to know with great certainty how much carbon their forests contain when it comes to negotiating prices for carbon offsets.

“Peru’s minister of the environment can make very good use of this information,” says Enrique Ortiz, one of Peru’s leading conservationists and a senior program officer with the Blue Moon Fund in Washington, D.C., which supports global environmental projects. “It is a good proxy for creating mechanisms to reward good action, like which areas need to be protected and how to manage carbon trade. It also shows us where illegal mining is taking place, and that’s important, too.”

Asner and his Carnegie scientists used the CAO to map Panama’s carbon stock a year ago. But he says his maps of Peru are far larger and more accurate with potentially a broader impact.

“These maps suddenly place Peru at the very forefront of the challenge to combat climate change,” says Asner, whose 2013 TED talk on his aerial research has 522,000 views. “It’s a sea change in capabilities. It will enable the country to use its carbon stock as a tool for engaging the international community to slow the rate of deforestation and forest degradation through conservation.”

The importance of Peru

When it comes to the global environment, it is difficult to overstate Peru’s importance. Its Amazon jungles are deemed among the most biodiverse on earth in terms of tree, plant, animal and bird species. It also has the world’s fourth-largest store of tropical forests, behind only neighboring Brazil, the Congo and Indonesia. Critically, tropical forests soak up and store carbon emissions from industrialized countries. In doing so, they are an irreplaceable line of defense in slowing the rate of rising temperatures due to global warming.

The Carnegie report also comes at a critical time for Peru. While still largely poor, Peru’s economy is the fastest-growing in Latin America in part because of the prevalence of mining for minerals and drilling for fossil fuels. Those industries, which flourish as trees fall, helped put Peru at the top of another list — a leader among Amazonian countries in deforestation rates. The country lost some 400,000 acres in 2012.

To keep its economic growth rolling, the Peruvian Congress stunned environmentalists by passing a law on July 11 that reduces the authority of its Ministry of the Environment. The new laws could make it easier for mining and drilling activities to increase in forested lands, and make it more difficult to add additional protected land to Peru’s large inventory.

“Despite making good steps in regards to both economic growth and environmental protections over the last 20 years, these new laws show a lack of consistency and add doubt regarding the direction we are going,” says Pedro Solano, director of the influential Peruvian Society for Environmental Law in Lima. “Our environmental policy is still strong, but now politics will dictate more decisions.”

All this comes as Lima is preparing to host in December the 20th annual Conference of the Parties (COP) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The COP culminates in Paris in 2016 when the group will seek binding international agreements akin to the Kyoto Protocol signed in 1997.

In Lima, policy makers at the COP will negotiate amid the pressure of another looming deadline — the scientific community’s consensus view that widespread efforts to reduce carbon emissions must be implemented in the next 10 years to limit predicted global temperature increases to around 3 degrees F. If not, far worse droughts, hurricanes and sea-level rises than we’re already experiencing are anticipated in the next 50 to 75 years..

In such a context, the Peruvian carbon maps created by Asner and his team take on a heightened importance. He says the maps can help place a competitive value on carbon, which he believes is the best, and possibly only, hope to keep large tracts of tropical forests intact. “I’m going to the COP as a delegate and I’m going to give these maps to everyone I can,” Asner says. “The negotiators need to see the truth about what they have to lose and what they have to gain.”

Tropical forests: stand or fall?

As I wrote for National Geographic NewsWatch, one of the cruel ironies of climate change is that countries that ring the equator — most of them poor and eager to develop — possess a valuable asset in fighting rising temperatures that can they only monetize if they destroy it: their tropical forests.

These lush, dense woodlands are incomparably important to our lives on earth. They pull greenhouse gases from the air and store them, thus slowing the rate of global warming. They play a powerful role in the water cycle, thus creating clouds that make weather around the world. They harbor and sustain the majority of the earth’s biodiversity, thus providing shelter and habitats to countless species of wildlife and plantlife. And they provide these vital ecological services to all of us on the planet for free.

But these forests routinely sit atop lucrative troves of fossil fuels or minerals. Or they cover land that when cleared can be used for cattle ranching and palm-oil farming. Often, the governments in these countries, staring at high poverty and unemployment rates, chose revenue over conservation.

When that happens, a double whammy occurs. What was once a carbon sponge becomes a sieve. When trees fall, they release their carbon. Global deforestation contributes an estimated 17 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions, remarkably on par with the combined fuel burned in cars, trucks, trains and airplanes, according to the EPA.

Converting carbon to dollars

Asner believes that the high-resolution carbon maps he is producing can play a crucial role in changing the economic dynamic in tropical countries. If you know how much carbon is locked up in your forests and vegetation — in Peru’s case, his report estimates the amount at 6.92 billion metric tons — you can better place a value on it. And choose conservation over development.

“All the data Greg (Asner) is generating is being converted into knowledge about the carbon cycle,” says Miles Silman a tropical biologist at Wake Forest University who contributed field data to Asner’s report. “And that knowledge is being converted into how we think about remediating global climate change. We do that by converting carbon into dollars. We allow countries and enterprises to make an investment or get paid to keep forests standing.”

Asner picks up the thread: “The truth is, carbon is now worth about $6 a ton on the voluntary market. That’s pretty low. It’s worth so little because there is a huge uncertainty based on where the carbon is and how much is there. By offering really precise details about the amount of carbon in Peru and where it’s located, it has a chance of being worth a lot more.”

Economists speculate that when carbon returns to or exceeds its peak value in 2006 of $32 a ton, and when carbon offset policies take hold as a vital international strategy in battling climate change, countries like Peru will be rewarded for protecting their forests instead of allowing them to be plowed under. But such international strategies involving carbon offsets are far from reality. Among the best hopes appears to be REDD, the slow-moving, decade-old U.N. program of “reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation.”

There is both a supply and demand side to REDD. On the supply side, countries like Peru must show how much area they are saving from deforestation and prove that the land will remain protected. On the demand side, industrialized countries that exceed their annual agreed-upon carbon emissions must be ready to pay countries like Peru for the land it’s preserving in return for carbon offset credits.

But the financing mechanisms and national emissions caps to make REDD work do not exist.

“We want to push this ahead in Lima (at the COP) this year and try to get a (global financing and emissions) agreement next year in Paris,” says Chris Meyer, a expert on REDD policy with the Environmental Defense Fund. “To do this, we need to improve our ability to measure carbon stocks and density, and Asner is at the forefront of science in creating new technologies to provide these measurements.”

Will it help?

Alessandro Baccini, a remote sensing scientist with Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts, says that while national carbon maps have been produced before, the technology used by Asner and the Carnegie team allows for greater precision and accuracy.

“What is really important is the level of information that a country like Peru now has access to,” Baccini says. “It’s very enabling. It helps Peru really understand its landscape and understand the very best data out there for policy purposes — if they want to use it.”

Ideally, Peru will use these maps to steer development and extraction away from areas of highest carbon density; ideally, it will be rewarded by the industrialized world with carbon offset investments for doing so. Ideally, Asner’s high-resolution maps in Peru — which cost $1.2 million in private funding to produce — will be replicated in other countries dense with carbon-bearing tropical forests to help bolster the global carbon market and conserve more tropical forests..

“What’s important now is to ask: what will they do with it?” Baccini says. “Will it change the game? Will it open the eyes of the (Peruvian) government so that they say, “Gee, we can’t cut down these forests, look at how much carbon we’re losing.’? We’ll see.”

Justin Catanoso is an environmental writer based in Greensboro, N.C., and director of journalism at Wake Forest University. His reporting is sponsored by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reportingin Washington, D.C.

Facebook comments