The Fifth Assessment Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Friday, 31 October, 2014 - 11:59

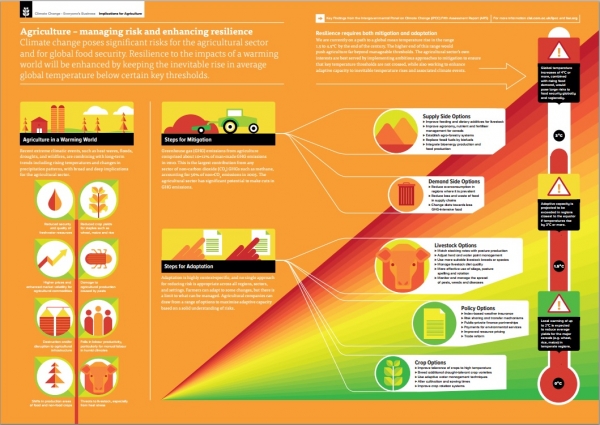

The Fifth Assessment Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is the most up-to-date, comprehensive and relevant analysis of our changing climate. The effects of climate change on crop and food production are already evident in several regions of the world, with negative impacts of climate trends more common than positive ones. This briefing explores the specific trends that will affect the agricultural sector.

Downloads:

- Briefing (pdf)

- Infographic (pdf)

- Briefing and infographic for high-quality print (zip)

- Presentation slides (pdf)

Executive Summary

The effects of climate change on crop and food production are already evident in several regions of the world, with negative impacts more common than positive ones. Without adaptation, climate change is projected to reduce production for local temperature increases of 2°C or more (above late-20th-century levels) up to 2050, although individual locations may benefit. After 2050, the risk of more severe yield impacts increases and depends on the level of warming. Climate change will be particularly hard on agricultural production in Africa and Asia. Global temperature increases of 4°C or more, combined with increasing food demand, would pose large risks to food security globally and regionally. Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture comprised about 10–12% of global GHG emissions in 2010. The sector is the largest contributor of non-CO2 GHGs (including methane), accounting for 56% of non-CO2 emissions in 2005.

Opportunities for mitigation include so-called ‘supply’ and ‘demand’ side options. On the supply side, emissions from land use change, land management and livestock management can be reduced, and terrestrial carbon stocks can be increased by sequestration in soils and biomass. Emissions from energy use across the entire economy can be reduced through the substitution of fossil fuels by biomass providing certain conditions are met. On the demand side, GHG emissions could be cut by reducing losses and waste of food, and by encouraging

changes in diet.

The agricultural industry’s own interests are best served by implementing ambitious approaches to mitigation to ensure that key temperature thresholds are not crossed, while also working to enhance resilience in the face of inevitable temperature rises and associated climate events. While adaptation to climate impacts is possible, largely by extending techniques already in existence, there is a limit to what can be managed. Adaptive capacity is projected to be exceeded if temperature increases by 3°C or more, especially in regions close to the equator.

Conclusion

Overall, climate change is projected to cause food production to fall, with lower yields from major crops. These projected impacts will occur in the context of simultaneously rising crop demand, which is projected to increase by about 14% per decade until 2050. Without adaptation, local warming of up to 2°C is expected to reduce average yields for the major cereals including wheat, rice, and maize in temperate regions. Impacts are expected to lead to increased pressure on freshwater resources, price and market volatility, further damage to production from weeds and pests, and substantial losses to land-based ecosystems and the functions they provide.

In 2010, governments agreed a target of keeping the rise in average global temperature since pre-industrial times below 2°C, which implies the necessity for major cuts in GHG missions. The agricultural sector has enormous potential to make cuts. Land-related mitigation strategies from combined action on agriculture, forestry, and bioenergy could contribute 20–60% of the total emissions reduction needed by 2030 to put society on a trajectory compatible with the 2°C target. A further cut of 15–45% is feasible by 2100. Action to reduce emissions while building adaptive capacity needs to be managed with care as multiple barriers to progress remain, and there is a danger that climate progress could be made at the expense of other sustainability concerns including food security.

Efforts to reduce hunger and malnutrition will increase per-capita food demand in many developing countries, and population growth will increase the number of people requiring a secure and nutritionally sufficient diet. Thus, a net increase in food production is an essential component for securing sustainable development. How to manage this at a time when emissions need to decrease rapidly will be challenging.

Although this summary report deals with resilience and mitigation separately, the agricultural sector has the option of dealing with both simultaneously. As AR5 illustrates, adaptive capacity is projected to be exceeded in low-latitude areas with temperature increases of more than 3°C. As a consequence, the agricultural industry’s own interests are best served by implementing ambitious approaches to mitigation to ensure that key temperature thresholds are not crossed, while also working to enhance adaptive capacity to inevitable temperature

rises and associated climate events.

Work regions:

Mountain Ranges:

Location Country:

United States

Files:

Facebook comments